USS pension scheme and fairness

The Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) is among the largest pension schemes in the UK. It provides pensions for academic and other staff in most of the UK’s universities — and right now it is the subject of strike action in around 60 universities. The strike relates to substantial proposed changes to the pension scheme.

Most of the current arguments are about the long-term affordability of USS in its present form. I do not consider myself sufficiently expert to add much that would be useful on that (crucial) aspect of USS — so that’s not the subject of this post. Instead, here I will take a look at the current USS scheme in regard to aspects of fairness; and I’ll examine the new proposals and their implied direction of travel, in relation to fairness.

Why am I writing this? Well, I needed to find out enough about USS and the new proposals to be able to explain — to friends, family, colleagues in other countries, etc. — what all the current argument is about. One thing I found — quite separately from the arguments about affordability of a defined-benefit pension scheme — was that the new proposals seem to have the wrong direction of travel in relation to (at least my notions of) fairness.

At the end I’ll make a specific suggestion towards improving the currently proposed changes to USS.

1. A bit of history

Back in the mists of time, when I first joined USS, the university that appointed me was (rightly) very keen to stress how great the pension scheme was. I would need to pay 6.35% of salary, and the university would contribute an additional 18.55% of my salary, to provide a guaranteed pension based on whatever salary level I had achieved at retirement. This was regarded as an important part of the deal: our salaries were considerably lower than we could be paid elsewhere, but the promise of a decent pension would compensate to some extent.

I remember well, a few years later in 1997, the widespread feeling of outrage and dismay when the universities collectively decided to reduce their contributions from 18.55% to 14%. In 1997 the USS pension fund was substantially in surplus, and the universities succumbed to the natural temptation of a ‘contributions holiday’. (It turned out to be a very long holiday: the universities’ contribution rate remained at 14% until 2011.)

Right now, in 2018, employer contribution is 18%, and USS members themselves pay 8% of salary into the scheme (with an option to increase that to 9% in return for a matching 1% increase of the employer contribution to the USS member’s “defined contribution” account with USS).

In relation to this history, let me mention here two aspects relating to fairness:

-

The ‘final salary’ basis for determining the amount of pension payable was (in my opinion!) blatantly unfair. As someone who stands to benefit from it, I think I am in a good position to say this. Members’ life-long contributions to USS were being used disproportionately to pay the pensions of those who were paid the highest salaries, and especially those whose salaries became high relatively late in their careers.

-

The long contributions holiday taken by universities between 1997 and 2011 is clearly connected with whatever problems USS has today. The universities ought to be prepared to substantially increase their contributions to the USS pot when the historic surplus has been run down partly as a result of the earlier (substantial!) ‘holiday’. It would be completely unfair to expect future USS members to pay the cost of the ‘holiday’.

2. Current USS

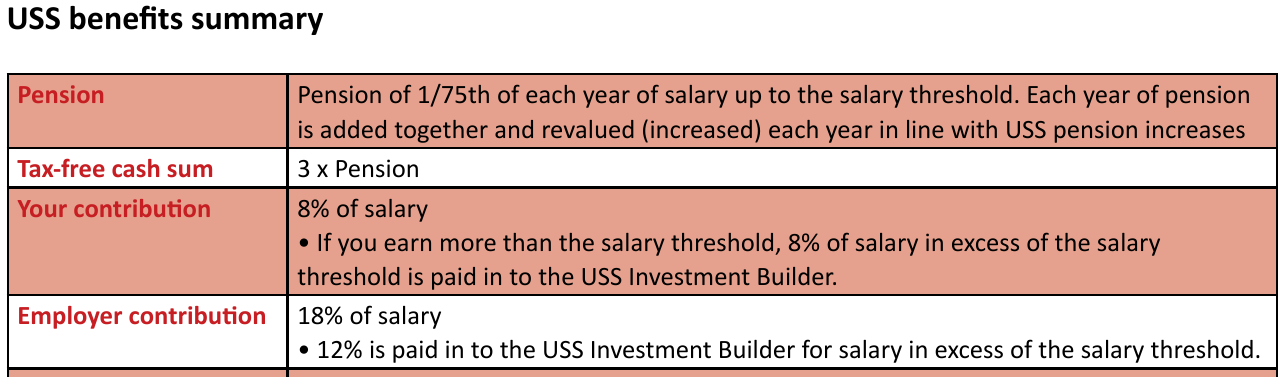

This excerpt from https://www.uss.co.uk/~/media/document-libraries/uss/member/member-guides/post-april-2016/a-new-employees-guide-to-joining-uss.pdf gives a very rough summary of the current USS setup:

In relation to fairness of the current setup, I want to note three things:

-

The unfair final salary aspect has now gone (following the changes to USS that were made in 2016). Instead, we now have ‘Career Revalued Benefits’ (CRB), based on contributions from annual salary up to the ‘threshold’ amount of around £55k. This results in lower pensions for many (perhaps most) USS members, especially those whose salaries increase substantially in mid-late career. But CRB does seem a fairer basis than ‘final salary’, for determining the relationship between life-long contributions and the level of pension ultimately provided. (The 1/75 multiplier is arguably not high enough; but that relates more to affordability than to fairness.)

-

The current USS setup has an appealing, progressive aspect: the employer contribution of 18% supports only a 12% contribution to the ‘USS Investment Builder’ pension pot that relates to to annual salary in excess of the £55k threshold. The implication of this is that some (maybe most?) of the remaining 6% of employer contribution, for salaries over £55k, gets used in support of the defined-benefit CRB scheme that applies to the first £55k of every member’s salary. As a principle, this seems right and fair: a priority for USS should be to ensure that even the least well-paid members get a decent pension. Appropriateness of the precise details (12% versus perhaps some lower figure or a decreasing schedule for higher salaries; and the £55k level of the salary ‘threshold’) is of course open to debate, still.

-

The previous two points were about ways in which USS currently is fair. For balance, let me mention one aspect of current USS that does seem unfair, still. The USS scheme has always, as far as I know, included specific pension provision for the surviving spouse/partner and/or other dependants of a member who dies. While this clearly is a benefit to those members who have got such dependants, it implies some level of subsidy from the contributions — whether made directly, or by the employer — of any member without such dependants. (Again I write as someone who does benefit from this; but I don’t regard it as fair!)

3. The USS proposals for change

The following excerpt is from https://www.uss.co.uk/how-uss-is-run/valuation/2017-valuation-updates/proposed-changes-to-future-uss-benefits:

My thoughts on the specific numbers there, in terms of fairness, are as follows. (The first item in the following list is by far the most important of the three; the other two are quite minor by comparison.)

-

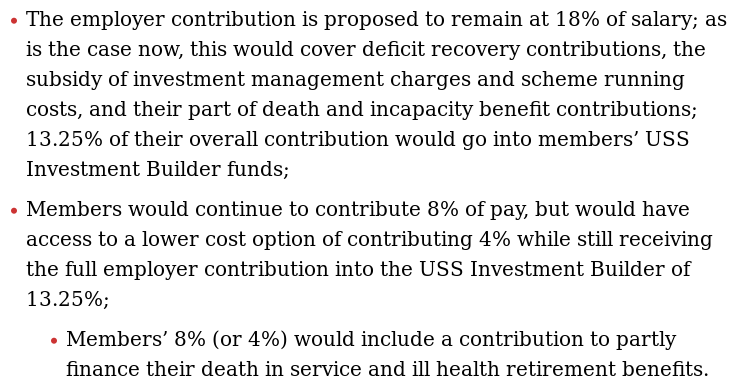

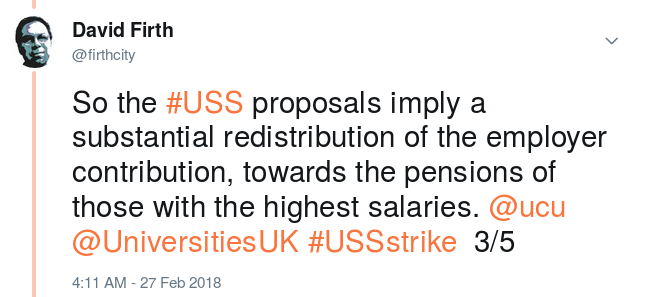

For salary amounts over the current threshold of £55k, the proposal would actually increase the employers’ pension-pot contributions (from the current 12%, to 13.25%). This runs counter to the ‘progressive’ aspect, mentioned above, of the current USS setup. Moreover, it implies that less of the employer contribution on salary amounts over £55k — that is to say, less than now — would actually be used to service the defined-benefit commitments of USS. This seems absurd. It represents a direction of travel that’s completely unfair: it would systematically shift the future cost of those defined-benefit commitments, away from the higher-paid members, onto those whose salary is mostly or entirely below the current £55k threshold.

-

The suggested flexibility to adjust member contributions downwards to 4%, while still getting 13.25% employer contributions, looks good on the face of it. But who would it benefit most? Most members with low to middling incomes will probably want or need to contribute 8%, still, in order to (aim to) ensure that they have a decent pension at retirement. Probably the main beneficiaries of this flexibility would be those members with the highest salaries, who could use it to reduce or eliminate potential breaches of the HMRC allowances (either the Annual Allowance for pension contributions, or the Lifetime Allowance for total pension-pot size).

-

That last bullet-point in the above excerpt looks relatively minor. It suggests shifting some of the cost of USS death benefits away from employers, to members — if I have understood it correctly. The details of this are not yet clear, at least to me; but it could imply that the cost of pensions for widows/partners and other dependants — which I have argued above is already unfair — would be carried more directly than before by members, i.e., through their own direct contributions rather than their employers’.

4. Conclusions

My comments in this post really are quite separate from the on-going arguments about affordability of the defined-benefit part of USS. But…

If those arguments about affordability do result in substantial changes being made, then I really hope that considerations of fairness will play a major role. As things stand at present, the proposed USS changes would appear to be quite neutral or even beneficial to those members with the very highest salaries, but clearly detrimental to the majority.

A more positive take on the points made above would be that there is plenty of room for manoeuvre, towards the negotiation of a future USS that could work better for all. The universities plainly are not currently at the absolute limit of what is affordable. The proposal to contribute more to the pension pots of the highest paid, rather than less, makes this abundantly clear (as indeed does the USS history, as mentioned above). A future USS that’s designed to be more progressive than the present version — i.e., with the highest paid receiving gradually lower marginal rates of employer contribution to their pension-pots — could perhaps make the defined-benefit component of USS work out to be (even more) clearly affordable?

Update (4 March 2018): The follow-up post Future USS: Robin Hood can help? formulates a concrete suggestion along the lines just indicated above — a simple device that would make USS both fairer and more affordable.

Update (16 March 2018): After reading this post, you might perhaps be interested in some of these follow-ups:

- Future USS: Robin Hood can help?

- Latest USS proposal: Who would lose most?

- USS proposals: Tail wagging the dog?

- Simple maths of a fairer USS deal

© David Firth, February 2018

To cite this entry: Firth, D (2018). USS pension scheme and fairness. Weblog entry at URL https://DavidFirth.github.io/blog/2018/02/26/uss-pension-scheme-and-fairness/.