My best known work, fading citations and a bit of history

This will be the second egocentric post in succession — for which, apologies in advance! (It’s a sign of age, I suspect.)

This year will see the 30th anniversary of the publication of my most-cited research paper, which developed a general method for bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. I’ll write a few notes below (section 2) about the paper’s history. But first, to the main reason for this blog post: something that seems odd in the recent citation data.

1. Why does citation growth seem to be slowing?

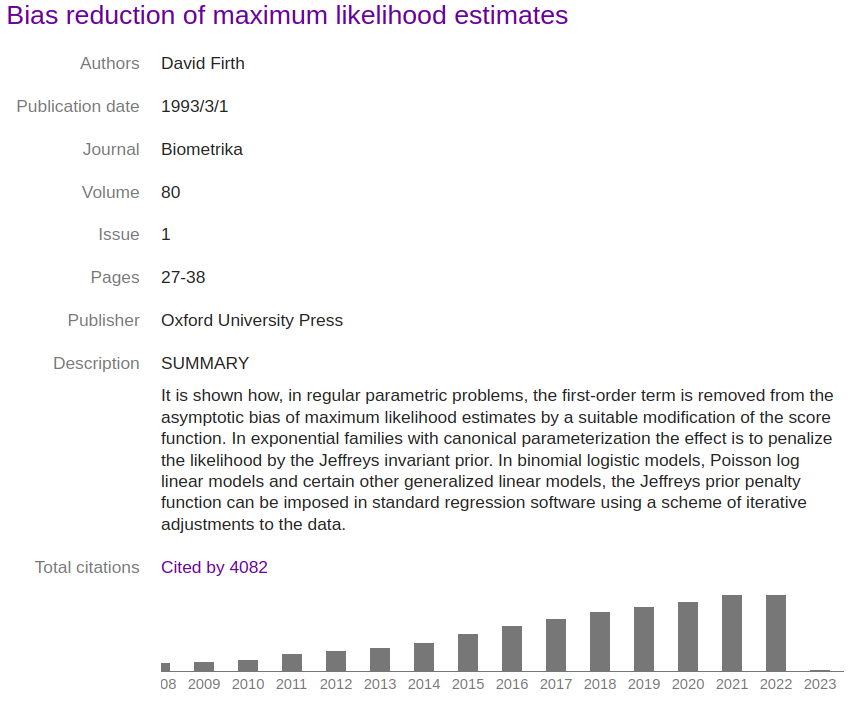

Here is today’s view of the paper in Google Scholar:

The graph there indicates that my 1993 paper is still cited — Google Scholar shows a steadily increasing annual count, reaching 494 citations in calendar year 2021. The count shown for 2022 is currently 491 citations, and I suppose that that figure might grow a bit in the early days of 2023 as Google Scholar catches up. But it does look as though the growth in citations is slowing down a bit.

Why does this seem odd? Well, I know from interacting with other researchers (at conferences for example) that usage of the method from my 1993 paper is still on the increase, as is the range of research disciplines in which it gets used. So the puzzle is: why does the Google Scholar citation count no longer seem to show sustained growth in the method’s use?

At one recent conference I attended, I met someone who told me that “Firth logistic regression” (as they called it) is now so standard in their field (a particular branch of medical research) that it often gets used without any explicit reference to my published work. For example, a published research article might say something like “we used Firth’s logistic regression” but then not cite my 1993 paper as the source of that method.

If that’s the reality, then I suppose I ought to be happy about it. I am guessing that the use of (for example) “Fisher information” and “Cox proportional hazards model” — each of which is often seen without reference to the source (Fisher 1925 or Cox 1972 respectively) — did not make Fisher or Cox very unhappy. If it turns out that I have published something in remotely the same league as those things — even if it’s in one of the lower divisions of the league! — then I should not be at all bothered about citation counts.

To see if there is any concrete evidence for what I had been told at the recent conference, I took a quick look today at the data for the current year, 2023. It’s actually only the 5th day of 2023 today, so there is not too much data — a big advantage! (While more data would likely yield a more reliable analysis, the fact is that much more data would have taken much more time to process, and that would have been prohibitive for me.)

The 2023 data, as at 5 January

Google Scholar records 7 citations of my 1993 paper so far, in the first 5 days of 2023.

But a Google Scholar search for any papers whose text includes the words “Firth” and “logistic” finds 10 papers published in 2023 to date. All ten of those papers do indeed use the method that was developed in my 1993 paper. But only two of the ten papers actually contain a citation to my published work (they both cite the 1993 paper, so they are included among the 7 mentioned above). The remaining eight papers are “non-citing”: they all describe their use of “Firth’s logistic regression” or “logistic regression with the Firth procedure” or suchlike, but with no reference provided to the published source of the method.

(The ten papers that were found in the just-mentioned search are listed here in search-results.txt, in case anyone is interested!)

To sum up this little data-collection exercise, then:

- in total fifteen distinct papers were found that used my method;

- seven of them cited my 1993 paper, and eight did not.

Conclusion?

It’s a tiny amount of data that I have looked at here, but seemingly already enough to confirm what I had heard anecdotally at the recent conference: there appears to be plenty of published research that uses the method from my 1993 paper but without citing its source. Indeed the evidence just presented, small as it is, suggests that non-citations possibly outnumber formal citations at present.

There could perhaps be an interesting project for a data-science student in all this? For example, to look at citations of the famous Cox 1972 paper and the extent to which formal citation gets replaced by bare phrases such as “Cox proportional hazards model” or “Cox regression” or just “Cox model”. Such a project would demand/develop substantial skill in text processing, I think, and it might present some difficulties in terms of automated access to published works. But it could perhaps reveal some interesting patterns? (and similar patterns might even be found in other disciplines too?)

2. A bit of history

While writing the above I was reminded of various things connected with that 1993 paper. I’ll make a few notes here on some of them, in case anyone is interested.

Actually written in 1991

This I remember vividly. In May 1991 our first child was born; and her arrival was energising as well as exhausting. I wrote “Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates” in the late spring and summer of 1991. I think the sleep-deprived nights in that period might have caused me to think differently about things; I doubt that I would normally have had the confidence to write such a paper, at such speed. (I am normally very, very slow!) Our newly arrived daughter cartainly inspired me to finish the work and submit it to Biometrika for publication, by the end of the summer.

And then the paper was rejected, quite quickly as I recall (a “desk rejection”). The Associate Editor did not like it. The reason was that my paper had some superficial similarities with other work from the 1980s and early 1990s, work on “modified profile likelihood” methods for eliminating nuisance parameters in statistical models. I knew about those things, and had deliberately steered away from writing about them in my paper. My paper was an altogether more modest piece of work than the hugely impressive modified profile likelihood literature, and it could in no way be viewed as an alternative to all that. To me this was absolutely clear: the notion of bias is not even invariant to re-parameterization of the model, after all. But the Associate Editor seemed not to appreciate this, and so the paper was rejected.

Rejection led to dejection, and for some time afterwards I left the paper in a drawer untouched. But eventually I did something that I would not normally do: I wrote humbly to the Editor of Biometrika to ask them to reconsider. I knew that my paper was as good as anything I could ever produce; and I also knew that Biometrika was where I wanted my best work to appear. Fortunately, the Editor understood the point about bias and reparameterization, and I was permitted to submit a revised version of the paper that clarified the relationship with modified profile likelihood. That second version was enough, thankfully, to persuade the Associate Editor to recommend acceptance of the paper — but only after a further revision to remove the parts that I had added about the (non-)relationship with modified profile likelihood. The paper eventually appeared in the journal about 18 months after it was first submitted.

Roots: potatoes!

The idea for the paper came out of a coffee-time question that I had been asked by Sue Lewis, who was my colleague at Southampton and an expert on design of experiments. Sue was doing some consulting work with a company (Dalgety PLC), who had conducted a small experiment relating to the storage of potatoes. The problem was that their logistic regression analysis (performed in GLIM) had produced some enormous parameter estimates and standard errors, and their question to me was whether there was something wrong with the design of the experiment. I was interested, and found that the problem was not with the design but with the analysis: the well-known phenomenon of separation was causing maximum likelihood estimates to be “at infinity”. This led me to think about penalizing the likelihood to avoid the “estimates at infinity” problem; and then I made a connection with bias reduction, which led to the more general method that was developed in the paper.

I never actually wrote anything about the potato experiment, unfortunately. Several years later, though, the same dataset — with analysis by my method — appeared in a nice paper that Sue Lewis published with other members of her experimental-design group. It’s the “potato packing example” in their 2006 paper:

Woods, DC, Lewis SM, Eccleston, JA & Russell, KG (2006). Designs for generalized linear models with several variables and model uncertainty. Technometrics, 48(2), 284–292.

[A note for younger readers: GLIM was ground-breaking software, first developed in the 1970s under the leadership of J A Nelder and sponsored by the Royal Statistical Society. It was the first “object-oriented” system for interactive statistical modelling, and it led to a revolution in statistical practice. Today’s glm() and other such modelling functions in R, for example, are direct descendants of GLIM.]

Surprisingly wide reach?

The paper went largely unnoticed for about 10 years after its publication. But then it started to be used across a fairly broad array of research disciplines. This was largely due, I think, to the appearance in 2002 of an influential Statistics in Medicine paper by G Heinze and M Schemper from the University of Vienna — and due especially to their having published widely useable software to accompany their paper.

Heinze, G & Schemper, M (2002). A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Statistics in Medicine, 21(16), 2409–2419.

Papers in similar vein appeared also in some other disciplines. A notable example is this 2005 Political Analysis article by C Zorn:

Zorn, C (2005). A solution to separation in binary response models. Political Analysis, 13(2), 157–170.

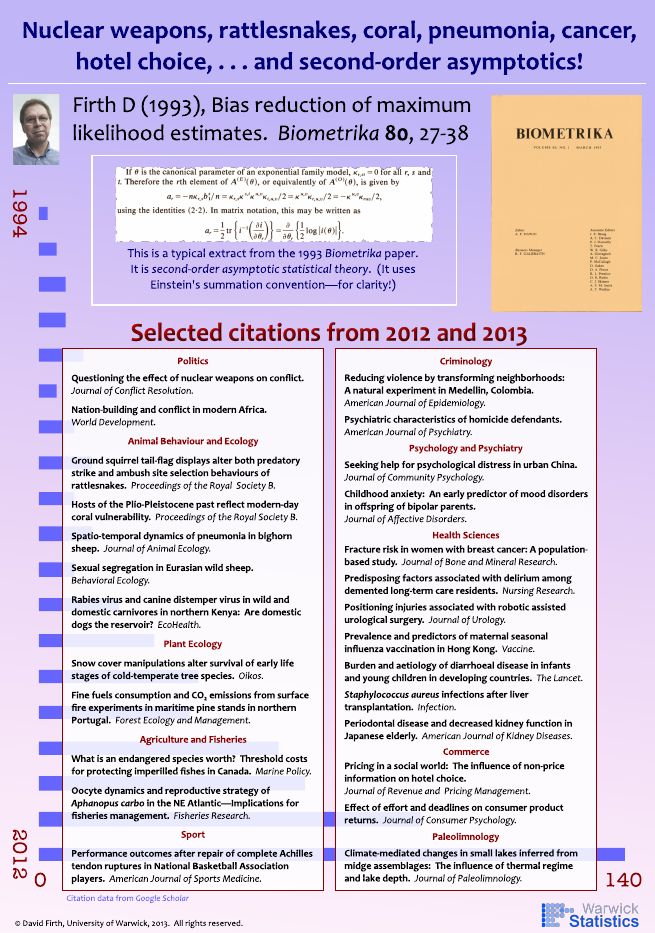

By 2012 my paper was being cited more than 100 times per year, which was both pleasing and unexpected. In 2013 I made a poster, for a departmental event at Warwick to showcase the applied impact of Statistics research. The poster (PDF available via the thumbnail link below) gave examples of several research fields in which the method from my paper had been used.

(The subliminal bar chart in the poster shows the Google Scholar citation counts for years 1994 to 2012.)

Most of the applications seen in other disciplines have been in the context of binary and multi-category regression models, especially logistic regression and multinomial-logit models. This is unsurprising, given the existence of accessible works of advocacy such as the papers by Heinze & Schemper (2002) and by Zorn (2005), mentioned above. In addition, logistic regressions (and similar) are a win-win context for estimation via the maximum penalized likelihood method of my paper. Finite estimates are guaranteed; and importantly, bias reduction is always accompanied in such contexts by variance reduction — so there is no trade-off between bias and variance. These features of the method had been known about for several years through empirical studies and informal arguments, and they are established more systematically in a relatively recent paper written jointly with Ioannis Kosmidis.

Kosmidis, I & Firth, D (2021). Jeffreys-prior penalty, finiteness and shrinkage in binomial-response generalized linear models. Biometrika, 108(1), 71–82.

And that brings us nicely back to citations. Of the “non-citing” publications, i.e., papers that use my 1993 method but don’t cite the 1993 paper, most (perhaps all?) are applications of logistic regression for binary-response data. And nowadays such applications really should be citing the newer work Kosmidis & Firth (2021). These things only happen very slowly of course, if at all. I’m not going to hold my breath…

© David Firth, January 2023

To cite this entry: Firth, D (2023). My best known work, fading citations and a bit of history. Weblog entry at URL https://DavidFirth.github.io/blog/2023/01/05/f93-citations-and-history/